The last thing I wanted to do is to start writing about gear, especially camera gear since the web is now surely beyond saturation point with that kind of stuff. However, I do confess to being partial to the occasional gadget from time to time, the latest one being the Suunto Core wrist-top computer that woke me up at 5:00 yesterday morning with an ominous storm warning. As well as a barometer/altimeter, it also has a compass and sunrise/sunset times, which makes it great for landscape photography.

Ironically, one of the reasons I bought it is that I’ve lost faith in electronic gadgets in general. After being seriously let down by my iPhone on a variety of occasions, I’ve come to view it as something of a bonus when these things work rather than anything to be taken for granted. It seems to me that the more complex and all-powerful devices become, the more they develop an uncanny ability to let you down when you need them most. The Suunto does a handful of things and it seems to do them well, so I feel it is a bit different.

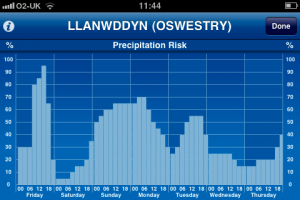

One thing that I do use quite a bit on the iPhone is WeatherPro, an excellent and really quite accurate source of information that doesn’t seem readily available elsewhere. As an example, I found a small window of opportunity this morning (Saturday) to get some photography done before another band of rain, quite possibly triggering another Suunto storm warning.

Of course, the truth is that even with all the gadgets in the world, you still need to get out there, which brings to mind the wonderfully anti-gear maxim “f/8 and be there”. It’s both amusing and depressing to see how many people on the internet seem to get hung up over the “f/8” part.

“Be there” can also be interpreted in another sense with landscape photography, since chance plays such a part that it often pays to be open to the idea of serendipity and to be receptive to the opportunities that do present themselves. Sometimes it pays to abandon preconceptions in favour of what the landscape wants to say.

Even with this in mind, it surely makes sense to find ways to stack the odds in our favour; to improve the chances of being there. That is the real purpose of the gadgets and iPhone apps.