Old folk customs have a surprising tenacity in post-industrial Britain. It sometimes seems that rural traditions, like nature itself, have a latent irrepressibility, springing up incongruously through the fabric of modern society.

A few years back I read an account of a largely forgotten custom in which children wore a sprig of oak to school on the 29th of May. Known as Oak Apple Day, anyone who turned up in the playground that day without an oak twig would run the risk of being thrashed with nettles by the other children. The festival has its origins in the Restoration of the monarchy, after Charles II escaped the Roundheads by hiding in an oak tree, but like many folk customs it is also infused with pre-Christian symbolism. In Roger Deakin’s book Wildwood he describes the annual Oak Apple Day celebrations in the village of Great Wishford, where every year the villagers walk the six miles to Salisbury Cathedral to claim their rights to gather ‘deade snappinge woode boughs and stickes’ from Grovely Wood. In a ritual with clear links to paganism, the local houses and parish church are decorated with green oak boughs as part of the celebrations.

I was interested to see that Oak Apple Day has been chosen by the Woodland Trust as a date for everyone to visit, record and vote for their favourite ancient trees.

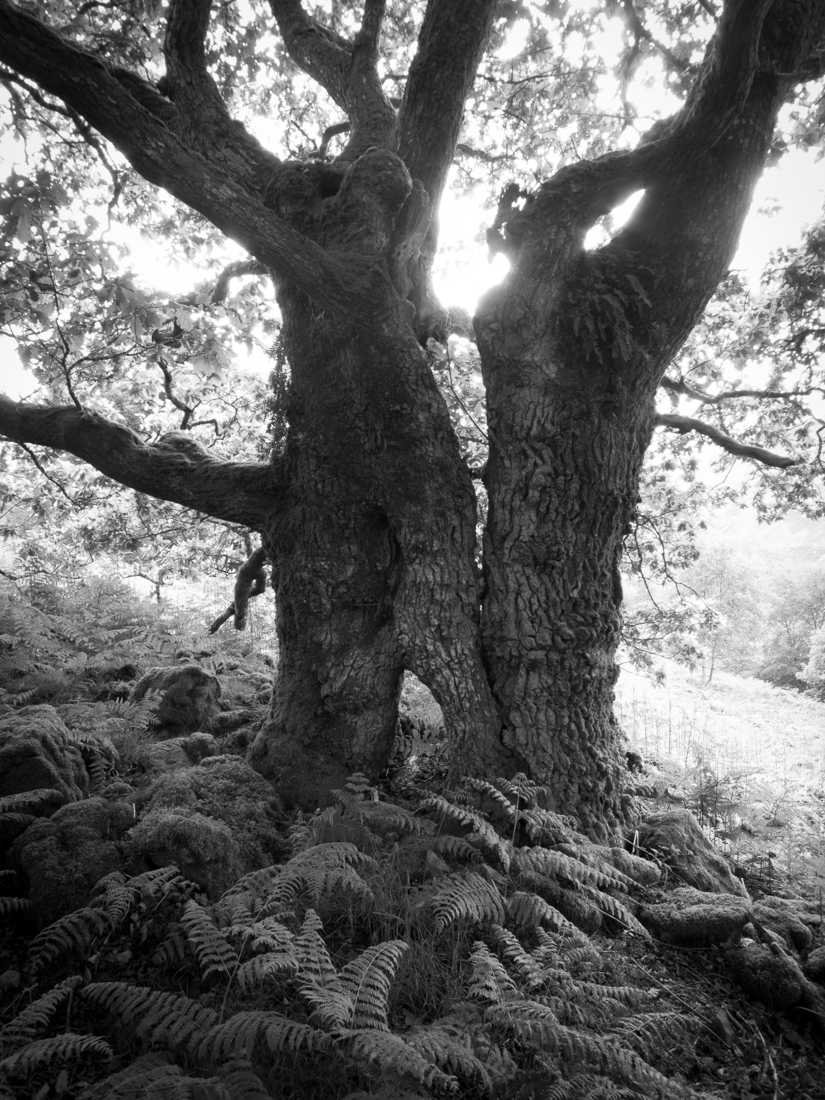

This is mine—a Common Oak which I like for its photographic potential. Partially straddling an old stone wall, it is a pollarded hedgerow oak and lies at the edge of a wood pasture on the Carngafallt RSPB reserve. Pollarding was widely abandoned over 200 years ago and, as can happen with neglected pollards, the tree is starting to split under its own weight.

This is mine—a Common Oak which I like for its photographic potential. Partially straddling an old stone wall, it is a pollarded hedgerow oak and lies at the edge of a wood pasture on the Carngafallt RSPB reserve. Pollarding was widely abandoned over 200 years ago and, as can happen with neglected pollards, the tree is starting to split under its own weight.

The ancient natural forests that once covered Britain had long disappeared by the time of the Domesday Book, but these woods and the nearby Cnwch woods have existed far beyond historical records. It doesn’t seem too much of a stretch to suppose that they may been wooded since the ice retreated in around 12,000 BC.

In the Western cultural imagination, woods have long been associated with wilderness. For centuries they existed as a forbidding boundary beyond the towns and villages—a place of magic and mischief. The Merrie Greenwood of medieval mythology, with its links to Robin Hood, Jack-in-the-Green and the Green Man carvings in churches and cathedrals reflects this uneasiness: a culture that feared the woods yet depended on them for its survival. The Anglo Saxon word weald or wold means a ‘wooded place’ and it is easy to see the common etymology with ‘wild’.

There is no wildwood left in Britain but it is encouraging to see a place where wildness still lives on in some form. The oak tree is a survivor, for the Cambrian Mountains can be a harsh environment. The recent winter was too much for the eucalyptus in my parents’ garden, which now stands as a stark reminder of nature re-asserting itself; a climate induced natural order of things.

At the edge of the wood, not far from my tree, I found the mysterious oak apple: the large round gall produced by the larva of the gall wasp.