A culture is no better than its woods.

—W. H. Auden

It’s mid afternoon and I’m sat in one of my favourite seats, looking west over the valley of Nant Cwmcidyn, the view towards Plynlimon framed with sessile oaks. The heather is in full flower and the bilberries hang heavy, covered in grey bloom and oozing their wine-coloured juices. Despite the recent cold nights, there is little sign of autumn here, other than the occasional brightly coloured russula poking through the moss. The woods, clothed in foliage and wrapped in the sleepy lull of late summer, are bird-less; near silent except for the drone of hoverflies in the canopy.

The seat has seen better days. Exposed to the elements and riddled with brown rot, it is near the end of its useful life. Wasps are everywhere, and a sign at the entrance to the wood warns of a nest close to one of the paths, its location painstakingly marked on an OS map. A light breeze ruffles the oak leaves. A hunting spider, egg sac on its back, darts through the leaf litter.

Somewhere above the woods of Coed Pen-y-banc, a small gap in the cloud opens, exposing towers of white cumulus behind. A weather system blowing steadily in from the south; the threat of more rain on the air. The tail-end of the morning’s downpour trickles to the valley floor through steep gullies lined with ferns and golden saxifrage, eventually joining the Trannon to the east of here, its waters peaty brown and foaming. To the side of the path is a fly agaric—the only one I have ever seen in these woods—its cap faded, the distinctive white flecks washed off by the rain.

The sessile oak woodland that once covered much of this area exists today only in small pockets, generally on the steeper slopes and ravines, and here at Coed Gwernafon, which is owned and managed by the Woodland Trust. More than a hundred ancient woods have been lost in Britain over the past decade alone, despite being some of our most ecologically important habitats and an irreplaceable part of our landscape and cultural history.

I have been a member of the Woodland Trust for a few years now, and I try to make the effort to visit this, my local wood, at least 3 times a year. Later in the autumn, it’s possible to find the beautiful Amanita citrina, the false death cap, under the oaks. But today I like this place simply because it is quiet. There is something meditative about being here, surrounded with the earthy smell of woodland after the rain.

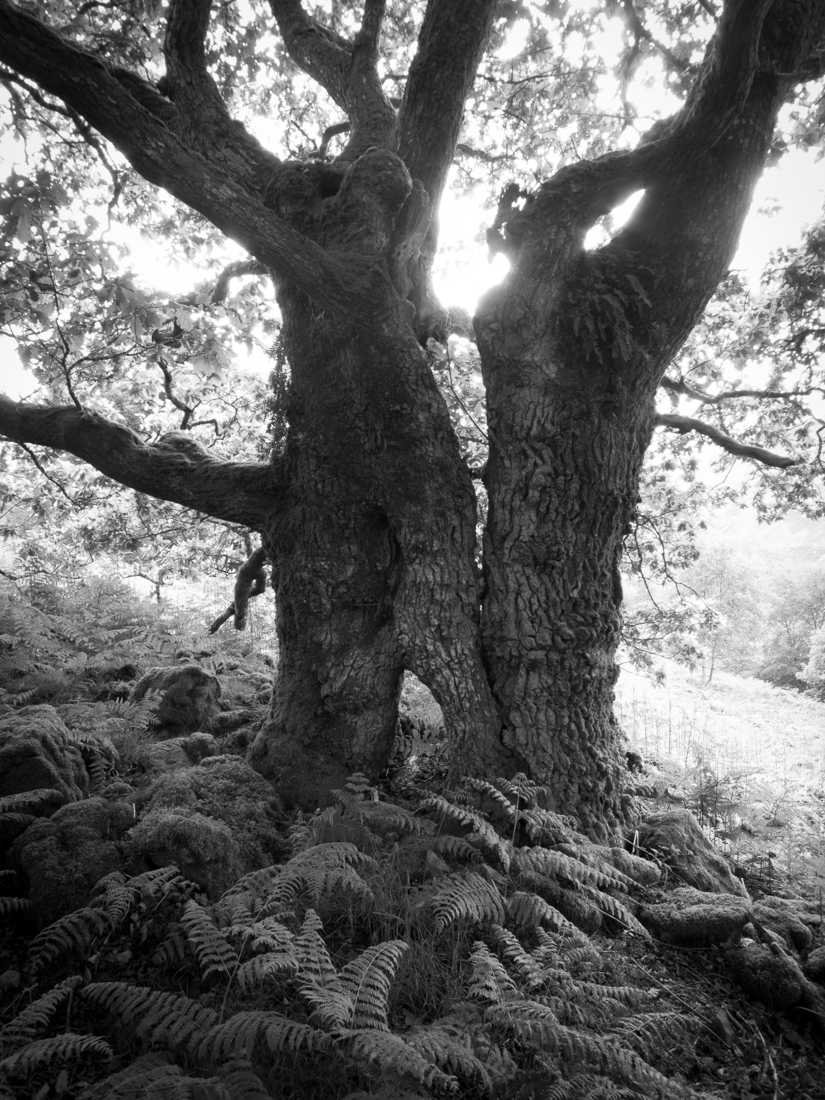

This is mine—a Common Oak which I like for its photographic potential. Partially straddling an old stone wall, it is a pollarded hedgerow oak and lies at the edge of a wood pasture on the Carngafallt RSPB reserve. Pollarding was widely abandoned over 200 years ago and, as can happen with neglected pollards, the tree is starting to split under its own weight.

This is mine—a Common Oak which I like for its photographic potential. Partially straddling an old stone wall, it is a pollarded hedgerow oak and lies at the edge of a wood pasture on the Carngafallt RSPB reserve. Pollarding was widely abandoned over 200 years ago and, as can happen with neglected pollards, the tree is starting to split under its own weight.

Originally planted in the 1940s, the forestry proved to be something of an ecological disaster for the rivers. Conifers were planted to the edges of the riverbanks, which, combined with extensive networks of drainage ditches caused acidification of the water and the widespread loss of aquatic invertebrates and fish. Steps are now being taken to correct this and the Forestry Commission are in the process of clearing conifers from the banks of the upper Severn.

Originally planted in the 1940s, the forestry proved to be something of an ecological disaster for the rivers. Conifers were planted to the edges of the riverbanks, which, combined with extensive networks of drainage ditches caused acidification of the water and the widespread loss of aquatic invertebrates and fish. Steps are now being taken to correct this and the Forestry Commission are in the process of clearing conifers from the banks of the upper Severn.